Spin.com: John Mellencamp, Painter The rocker from Indiana has become world-renowned for his paintings, with museum shows and a new Rizzoli coffee table book

Spin.com By Bob Guccione, Jr

In his early 20s, having just graduated from Vincennes University in his home state of Indiana, John Mellencamp went to New York to pursue one of two careers, either painter or musician. He brought demo tapes of him singing in bars, because he thought all he needed was to let people hear him sing to get a recording contract. And he had an appointment at the Art Students League of New York.

Tony Defries, David Bowie’s manager at the time, liked his voice and wanted to sign him. Art school, John discovered, was going to be expensive. “I had one set of people telling me I had to give them money, and the other was going to give me money, so I decided to go with the people who were going to pay me,” he said.

Defries got Mellencamp a record deal, no small thing in 1975, but insisted he change his name to Johnny Cougar. If he didn’t, there’d be no record. Reluctantly, John accepted the Faustian deal and the much ridiculed name. After a few hit singles, he broke out in 1985 with the album Scarecrow, recording under the name John Cougar Mellencamp. For his next album, The Lonesome Jubilee, another massive hit, he dropped Cougar and that tired old albatross sank to the bottom of the sea.

“For years, I really hated the fact that I signed with him and became Johnny Cougar,” he says now. “As I’ve gotten older, I realized the guy did me a favor. He gave me an opportunity to make records, and that name put a huge chip on my shoulder and made me work a little harder, and try a little bit harder.”

Although we may primarily know Mellencamp as a rock star, one of the highest-selling of all time and a Hall of Famer, he is also a great painter. Not a musician who also paints, God knows there are more than a few of those. No, John legitimately belongs in the Modern Art Pantheon, alongside the Rauschenbergs, Pollocks, Warhols, Hockneys and Frida Kahlos (he would be uncomfortable with that statement, but ignore that). His paintings sometimes echo the great German surrealist Max Beckmann, and sometimes Modigliani, and you might even think you saw the shadow of Basquiat fall over some of his pieces. Mostly John’s paintings are just his, just an American’s thoughtful, sometimes anguished, sometimes celebratory view of America.

I’ve known John for 35 years. We met when I went to Bloomington, Indiana, where he still lives, to interview him in 1987.

I had worked all night at the magazine and taken an early flight. He picked me up at my motel and we went to his house. It was a hot summer day, so he lent me a bathing suit and we sat by the pool to do the interview. He’d also been working all night, on The Lonesome Jubilee, and, like me, was very tired. At some point we both fell asleep — when I played back my cassette, there was us talking for about 10 minutes, then just birds chirping for the rest of the hour. One of us woke up and the scraping lounge chair startled the other. “I must be the most boring interview you’ve ever done,” he said to me, sheepishly. “I must be the most boring interviewer you’ve ever had,” I replied, embarrassed. We’ve been friends ever since.

I was also one of the first people he let see his paintings, which he had started doing again in earnest in the late ‘80s, but quietly, privately, and no doubt nervously. I was visiting him and he said, “Come here, I want to show you something,” and he took me to his studio and showed me what he had on the easel and lying around, stacked against a wall. “These are really good,” I said, and he said, pick one. I said, I can’t take one of your paintings! And he said, go on, it’s your Christmas present, if you don’t pick one I’ll just send you one.

I flipped through his canvases and said, “I love this!” It was a large painting of his family, including John as a little, mischievous-looking boy and his father, a stern, uncompromising-looking guy.

“Goddammit,” said John, “you picked the best one.”

I grew up around art. My father was a painter. Brilliant but failed. When he was in his early 20s he painted people’s portraits on the Spanish Steps in Rome for a couple of dollars. When I was born, we lived in a tenement in New York, on the seedy side of Greenwich Village, and my father painted, mostly my mother, sometimes in the bathtub which was in the kitchen, and other women, mostly naked. He didn’t want to sell the ones he considered best (and kept them until he died) and not enough people wanted to buy the rest, so he never made a living from it and eventually, years later when we were living in London, gave up the ghost and started Penthouse magazine.

John reminds me of what I remember of my father as a painter. There is a vortex of time and space, an alternate dimension, that artists disappear into, are allowed into, when they are truly creating. When they are making something that didn’t exist until they did it. This is so different from capturing what something or someone looks like, which is a skill but not creation. Real art, something that can take your breath away, a painting for instance that you saw 60 years ago but remember as clearly as if it was hanging on your wall, is as close to being God as a person can get.

And it’s an exquisite agony, a fraction of a second of being allowed to be God but then being kicked out, back into the street with the rest of the mortals streaming through the gray twilight of evening, their thoughts wrapped up in their simple, enduring, and perpetual purposes, unaware of the special few who, for the softest moment, kissed immortality.

Now, growing up around art, loving all art, and perhaps even fleetingly being artistic myself, doesn’t mean I understand art, or can reasonably, valuably, explain it. But who can! Other than the artist themself, who can really describe their creation? And even they often can’t, or just don’t need to.

Which is just as well, really, because John doesn’t think anyone knows what they’re flipping talking about anyway.

“There’s nobody that can look at one of my paintings, or anybody else’s, and pretend that they know what’s happening here,” he says. “All that they could say is, is it beautiful or is it not beautiful? That is basically what I think painting is. Art is for dreaming.

“When a painting is good, and I’ve said this before, it surprises the artist and it surprises the viewer. People should only look at the paintings and have the painting strike their imagination and not try to understand or criticize, condemn, or complain about what the artist has done. It’s not their place to do that because they are trying to understand and put together what’s inside of a man’s soul. That is not your job. There’s no one that can do that.

“Then for somebody to write about it is just wrong. How in the fuck do you understand a man’s soul? I was asked about Rauschenberg’s White Paintings and I just said, ‘I’m not qualified to talk on that.’ Rauschenberg was a guy who came at us with a different perspective and a different way of doing stuff.”

For the record, I say John’s paintings are beautiful, as you can see here for yourself.

I like his line how can you see into a person’s soul, although, of course, the irony is that is exactly what every artist presumes to do! With pure impunity! Artists are the cat burglars of the soul — they sneak into you, take whatever they fancy, and leave with it. Worse, sometimes they leave without taking anything, because they didn’t see anything worth taking.

This Is Gun Control

I asked him if he thought a painter had an obligation to be political.

“I’m not sure paintings need to be political at all.”

But a lot of his paintings are political, I point out.

“Some are, yes. I have a painting called So This Is Gun Control, and it’s a painting of [his son] Speck when he was a little kid being shot. Nobody likes that painting, but I felt like it needed to be said. I just used him as the subject because I had a picture of him laying in an awkward position on the ground as a little boy. I just used that, as he was contorted and laying weird, and I thought, ‘Oh, I need that shape.’ I knew how the legs would be and how the arms would be. He was in a concocted position.”

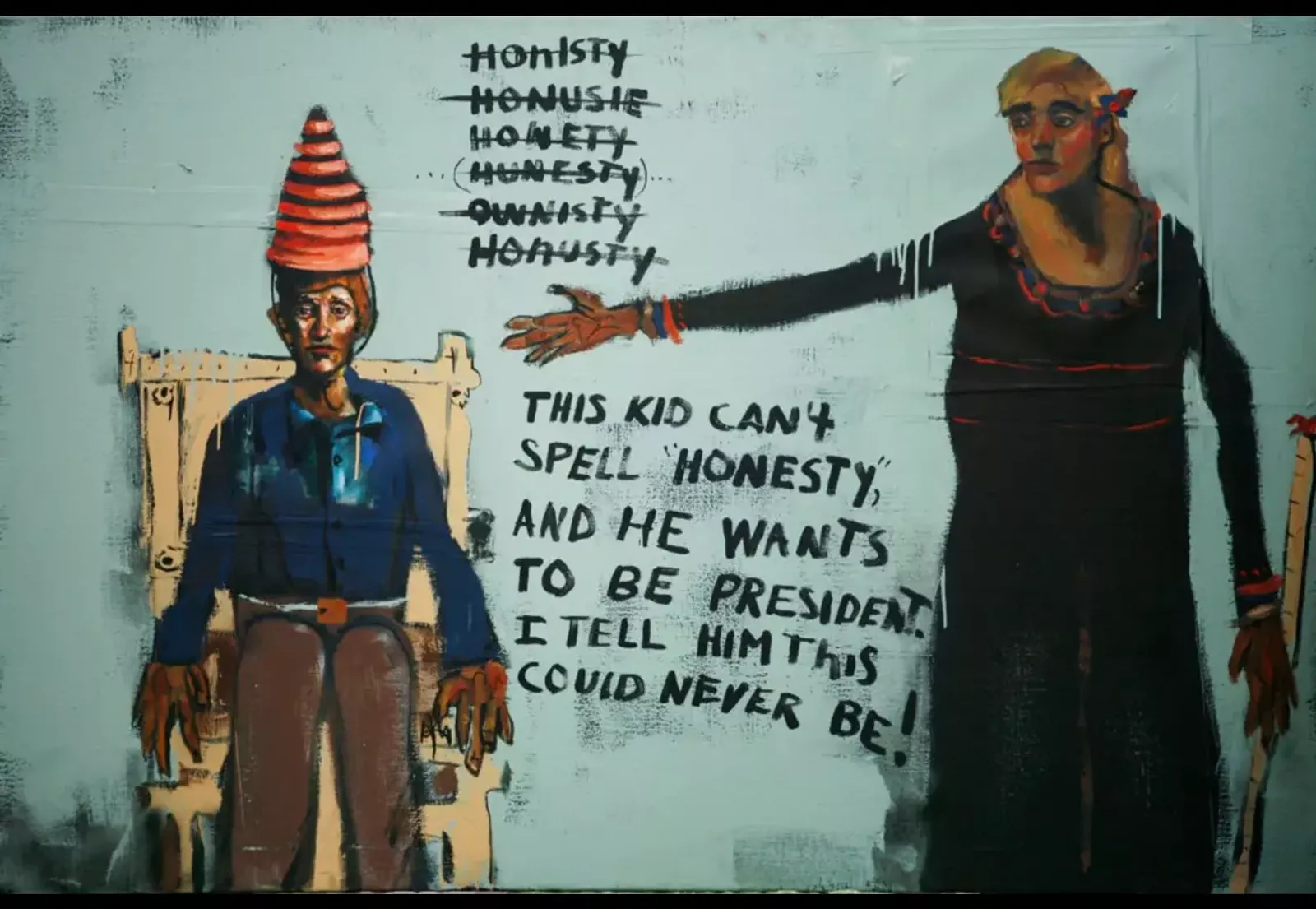

Paintings like Black on Black and Prairie Rose, and his current favorite American Odd, do seem political. In Honesty, what looks like a teenage boy with a beehive dunce’s cap sits on a makeshift throne, with what is presumably his mother standing next to him, and the text over the painting reads: “The kid can’t spell ‘honesty’ and he wants to be President. I tell him this can never be!”

And Martin Luther King, painted in 2005, bears the sadly true text: “Martin Luther King had a dream, and this ain’t it.” Strangefruit depicts a lynching, like the haunting Nina Simone song.

But his paintings, it’s probably accurate to say, are not overtly political. They express a point of view and you are left to deduce what you will. You may be pointed the way down a hall, but not told which room to enter.

He describes his painting as “a bit primitive, but to the point. That’s about all I can say. You may not like the point, you may think the point is good, you may not see it, you may not understand it, but ultimately and finally, I don’t give a fuck.”

As a songwriter and singer and performer, John Mellencamp had to carry around a huge anchor, and he succeeded both because of and despite being a not particularly glamorous, midwestern, somewhat cantankerous, preternaturally driven bit of a bastard, with a ridiculous stage name it took literally decades for people to forget. But because he also comes from that divinely gifted lineage of Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Bob Dylan, and Bruce Springsteen, the Olympian gods of American music, he succeeded wildly, unfathomably in some respects. But as a painter he has none of that weight tethering him to the churning muck. He is weightless and free.

It’s almost entirely accurate to say he is completely self-taught, but, as he points out, he had two weeks of instruction at the Art Students League of New York — they had an adult class that you could take, “and I was John Mellencamp and they let me take it,” he says. He studied under David Leffel, who took him under his wing. “I didn’t really understand anything that he was saying to me,” John says, adding that 30 years later he’s still trying to understand. His first show was with Miles Davis in L.A. — they hung the show together, which John remembers as being “very cool.”

“You have to learn the rules of painting. If you’re painting the human form, there are certain things that you have to do, the shadowing, whatever it is. You got to learn the rules and then you got to break them. Same goes for songwriting,” he says.

He doesn’t really have a specific process. “There’s rules that I follow for my paintings to turn out the way I want them to. I have learned to get out of my own way. When I was younger, I would be writing songs and they would start taking a turn a certain way and I’d go, ‘Oh no, no, no, we can’t go there, because that’s not where I want to go.’ Well, it turns out you have to let the painting or the song speak for itself.

“I don’t really care about the message. If the vessel sends me something with a message, I’ll follow it.

“Paint fast and make mistakes and then correct, correct, correct! A painting is a problem. You walk up to an empty canvas and you have a problem. To me it’s problem-solving. It says in that book God put out, we were put on Earth to toil and to work. I don’t believe everything in that book, but I think that’s good advice.”

Who’s your biggest influence as a painter, I ask?

“I would say there’s quite a few. Alex Putman, Jack Levine, Max Beckmann, Lucien Freud.

“I think that whether we’re conscious of it or unconscious, everything we see and everything we hear becomes — at least in my case — becomes mine. It goes through my filter and then I’ll use it in any fashion I like.

“You need truth somewhere to get started. It’s like building a house — if you use a faulty foundation, the house will fall down. If you don’t have that one true line, that is inspirational and means something to a song, or a painting, then probably you’re not going to be happy with the results.”

One of the things he loves about painting is it’s not collaborative, unlike making music, which, to some degree, always is. “It’s me, the canvas, the paint, and everything is down to the artist,” he says, in a very satisfied manner.

“Paintings are never finished, they are only abandoned,” he continues. “They’re abandoned because, I’ll be working on a painting and think, ‘Well, I need to go work on that.’ Then I walk upstairs after not seeing it for a day and go, ‘I think it’s done. Time to move on to something else.’”

Which is a higher art form, music or painting?

“I wouldn’t know. Painting seems to last a lot longer than songs because we have paintings from the 16th century and 17th century. We don’t have any songs from then. They’re there, but nobody knows them. Our generation can’t even name three Benny Goodman songs.

“The song is really the legacy. The painting is really the legacy. What people say about you, it really don’t amount to much. We are all in solitary confinement inside our own skins. We never really get to know anybody, we never really get to know ourselves. We’re just trying to figure out how not to, as the song says, waste our days.”

The Rizzoli book is an amazing body of work. And it doesn’t even scratch the tip of the iceberg. In the last many years he has been incredibly prolific. He paints so many portraits, does mix media collages, and makes three dimensional sculptures, which are like non-landscape dioramas. You get the sense that if the Fed Ex delivery guy lingers on the doorstep, Mellencamp will paint him before he gets back in his truck.

His portraits are distinct. He’s achieved the rank of those few artists that when you see one, you know they are his. The wide, sometimes sad, sometimes weary and emotionally full eyes, the hard lines of the faces, the clear weight of their lives. None of his figures have escaped life’s burden.

Texture is important. Some paintings have writing on them like lyrics. Some tell complicated, involved stories. If his paintings were songs you feel they’d be Tom Waits songs, growls of pleasure found in pain — and vice versa, I suspect.

In this book there are pictures of his ex-wife Elaine, nicknamed “Drainy” — and she looks drained. Hard, spiritless, more like a tree than a person. Meg Ryan, his former girlfriend, is radiant in his paintings of her, in a soft, unassuming way, more like the pretty girl next door who wanders over sometimes to hang out. She’s your friend too in his paintings.

John is the Alternate Universe Norman Rockwell. Pillowy adults and sprite-like children beam from Rockwell canvases, hopeful, content, and reflecting the brightest side of humanity. They’re a magnificent fantasy. John’s figures are wood stained in unheroic reality.

John after Heart Attack, 1994 is as forlorn a self-portrait as perhaps anyone has ever painted. The eyes are sallow, the shoulders slumped, and the proud corona of hair is gone, instead a thin outline of flat, dark hair covers his head. It suggests to me what you see in the mirror when you see, with absolute clarity, your own mortality. It’s not a happy picture, but it’s a beautiful picture, in the way a truly aching sad song can be so tremendously beautiful.

His paintings have so much quiet power in them. To me, they tell an American narrative, not all of it complimentary.

What is the soul of America, I ask him.

“Violence,” he answers. “This country was founded on violence, this country is run on violence, we spend more money on the war machine than anything else, people shooting people, people killing Indians and calling it their land, and taking the West Coast away from Mexicans by force. We’re a violent bunch of people.”

Is it because we have dark souls?

“I don’t know that it’s dark, it’s just what we are. Who’s to say what’s dark and light? I don’t know. America is a very violent country, and I’m not saying that everybody that lives in America is violent, but I’m saying this country was founded on coming in and taking. And there’s something almost cockeyed good about it. Come in and you take it.

“I got news for you, we’re not the greatest country in the world. We could tell ourselves that and we all like to believe it’s true, and maybe we were after World War II. Again, World War II was what, 80 years ago and an act of violence. An act of murderous fucking carnage and people losing their lives for a theory, something called fascism, something called democracy. Vietnam is the best example. We lost all kinds of people our age because of our government trying to protect us from communism, and now my son goes to Vietnam and Cambodia on holiday.”

My last question, I say to him, is one you asked me 30 years ago when I was at your house in Bloomington. “You said, ‘what’s your crown in Heaven?’ I’m saying that to you now, what’s your crown in Heaven?”

“A cigarette nine miles long.”

“Really? That’s it?”

“Well, the fix is in, me getting into Heaven. I’m not looking forward to dying. But my grandmother said when she was dying, ‘It’s not so bad, John, this dying.’ Of course she was ready to die. She was 100 years old.

“Grandma has been up there for a long time, and she told me,‘Buddy, by the time that you get up there, by the time you die, I will have been in Heaven for quite a long time and made a lot of friends and I’ll have a little influence, so don’t worry, you’re in.’ I said, ‘Okay, I’ll take you up on that.’ But she goes, ‘You got to try.’ I said, ‘I’ll try as hard as I can, Grandma.’”