The New Yorker: John Mellencamp’s Mortal Reckoning

The New Yorker - By Amanda Petrusich

In 2012, the singer and songwriter John Mellencamp was given the John Steinbeck Award, presented annually to an artist, thinker, activist, or writer whose work exemplifies, among other virtues, Steinbeck’s “belief in the dignity of people who by circumstance are pushed to the fringes.” The grace of the marginalized is a long-standing theme of Mellencamp’s writing. The musician, who comes from Indiana and began releasing records in the late nineteen-seventies, is known as a populist soothsayer, an irascible and unpretentious spokesman for hardworking, rural-born folks. Yet Mellencamp has also bristled at this characterization, which is largely rooted in fantasy: men gazing wistfully out the windows of vintage pickup trucks, watching dust blow by, listening to some parched and distant radio station. The image of such “real,” non-coastal Americans has become a useful cudgel for conservatives looking to depict their opponents as élitist buffoons; Mellencamp finds this grotesque. “Let’s address the ‘voice of the heartland’ thing,” he told Paul Rees, whose satisfying biography, “Mellencamp,” came out last year. “Indiana is a red state. And you’re looking at the most liberal motherfucker you know. I am for the total overthrow of the capitalist system. Let’s get all those motherfuckers out of here.”

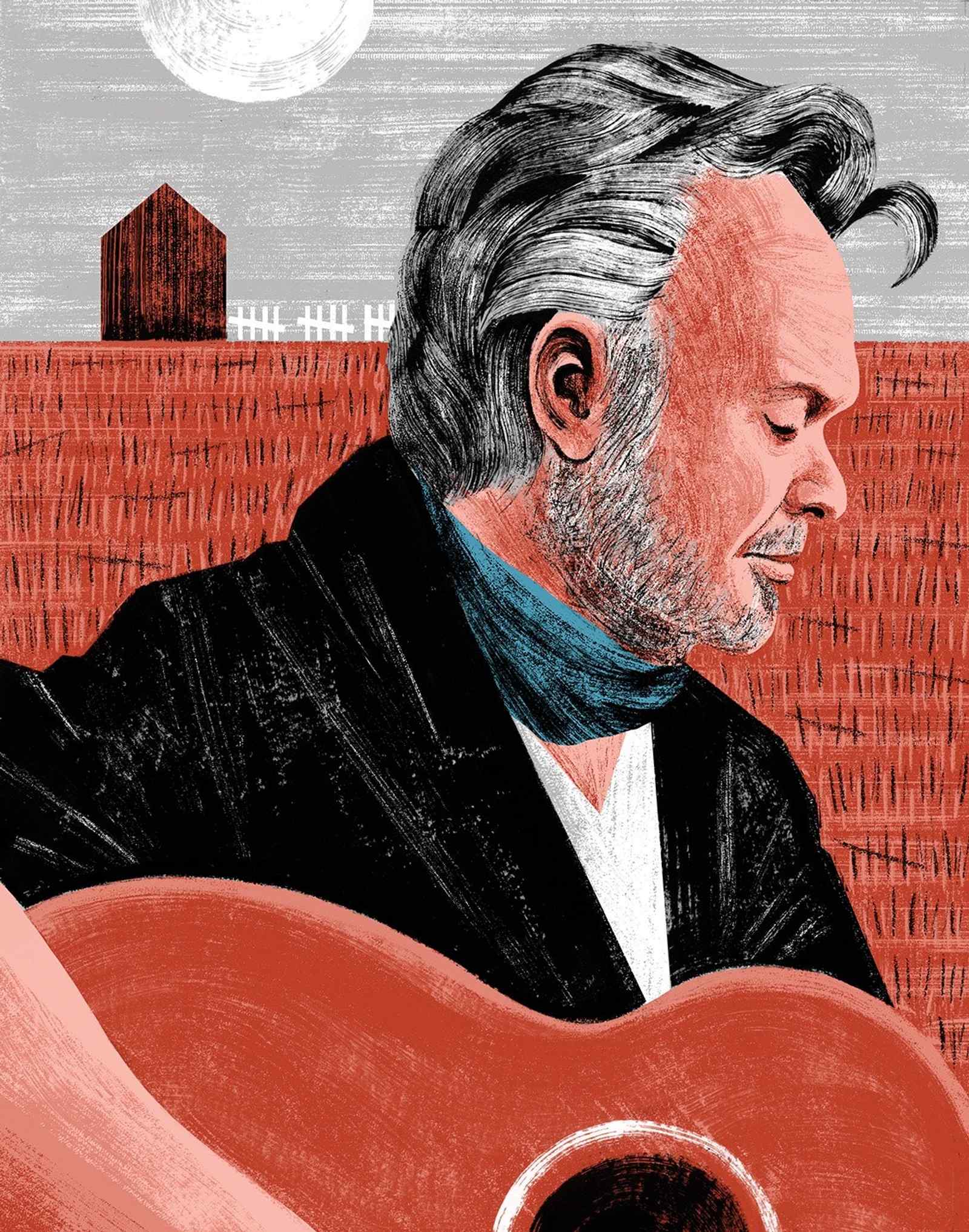

Besides sharing Steinbeck’s political radicalism, Mellencamp also possesses his instinctive knowledge of just how desolate even the sweetest life can feel. “All great and precious things are lonely,” Steinbeck wrote in “East of Eden,” from 1952. “Sometimes love don’t feel like it should,” Mellencamp sang on the single “Hurts So Good,” from 1982. Mellencamp turned seventy in October, and this month he is releasing “Strictly a One-Eyed Jack,” his twenty-fifth album. “Wasted Days,” the first single, a duet with Bruce Springsteen, is about the despair of aging. “How can a man watch his life go down the drain? / How many moments has he lost today?” Mellencamp rasps. “And who among us could ever see clear? / The end is coming, it’s almost here,” Springsteen adds. Mellencamp’s voice is shredded from decades of cigarettes—it remains an illicit delight to watch him smoke hungrily throughout an entire 2015 appearance on the “Late Show with David Letterman”—and his face has turned long and craggy under his trademark pompadour.

Mellencamp sounds like he’s working through a season of mortal reckoning, though, to be fair, he has been lamenting impermanence since his youth. On “Jack & Diane,” another single from 1982, he sang, “Oh yeah, they say life goes on / Long after the thrill of living is gone.” “Strictly a One-Eyed Jack” is lumbering, bleak, and engrossing. Mellencamp’s voice, once booming and raucous, is now softer, but never gentle. (Vocally, he has landed somewhere between late-career Bob Dylan and early-career Tom Waits.) He is frequently accompanied by acoustic guitar. Age seems to have given Mellencamp license to gripe; he is a poet of ennui, which makes him an apt mouthpiece for a moment when it is sometimes difficult to feel optimistic.

These days, Mellencamp doesn’t care about appearing likable, grateful, or good-natured. “I come across alone and silent / I come across dirty and mean,” he admits on “I Am a Man That Worries.” He delivers each line with the steadfast confidence of a guy who has witnessed a lot of ugliness and won’t pretend otherwise. As he told Rees, “I’ve been right to the top and there ain’t nothing up there worth having.” This sort of honesty—unconcerned with commercial striving; a pure repudiation of the filtered and staged—is rare. It buoys these songs and gives them heart.

Mellencamp was born in 1951, in Seymour, Indiana, with spina bifida, a neural-tube defect in which the spine and the spinal cord don’t develop properly. In the fifties, spina bifida was often terminal. It was standard practice to wait six months or longer to operate on infants with the condition, but, because so many babies were dying before then, a pioneering surgeon performed the procedure on Mellencamp right away. Incredibly, he survived. Rees’s book suggests that this early miracle gave the singer preternatural confidence. “Every day of my life my grandmother told me how lucky I was,” Mellencamp recalled to him. “You get told that enough and you believe it.”

Mellencamp’s family attended the Church of the Nazarene, a punitive Protestant sect that prohibited alcohol and tobacco. Even as a youth, Mellencamp had a reputation for being petulant and cocksure. By the age of fifteen, he was singing in a local band called Crepe Soul, six of whose members were Black. The band’s integration angered some listeners. “They loved us when we were onstage,” Mellencamp told Rees. “It was when we came off they didn’t like us so much.” Mellencamp learned to fight with a blackjack—a strip of leather with a piece of steel sewn into it. At eighteen, he married his high-school girlfriend, Priscilla Esterline. (The two later split, and Mellencamp married and divorced twice more; he has five children.) In 1976, Mellencamp acquired a manager, who suggested that he change his name to Johnny Cougar. He did, reluctantly, and signed a deal with M.C.A. Records. His début LP, “Chestnut Street Incident,” was a flop, and he lost both the manager and the deal. He didn’t become a pop star until 1982, when he released his fifth album, “American Fool.”

Mellencamp was a champion of so-called heartland rock, an earnest, vaguely melancholy mashup of traditional folk music and fractious, boot-stomping rock and roll. The sound was marked, lyrically, by concern for the working class and a realist approach to romance: there are no guarantees in life, so drive it like it’s stolen. The genre’s best songs unfold like short stories, with opening lines that tremble with foreboding. Lucinda Williams begins “The Night’s Too Long,” from 1988, “Sylvia was workin’ as a waitress in Beaumont / She said, ‘I’m movin’ away, I’m gonna get what I want.’ ” On Mellencamp’s “Small Town,” from 1985, he offers, “Well, I was born in a small town / And I live in a small town / Probably die in a small town.” Sometimes there are hints of redemption in the choruses. Often there aren’t.

Throughout the years, Mellencamp’s advocacy for the neglected began to focus on American farmers. In 1985, he, Willie Nelson, and Neil Young started Farm Aid, a nonprofit that puts on an annual benefit festival to bring attention to the plight of small family farms. In 1987, Mellencamp testified before the Senate in support of the Family Farm Act. He said, of frustrated farmers, “It seems funny and peculiar that, after my shows and after Willie’s shows, people come up to us for advice. It is because they have got nobody to turn to.” (Farm Aid operates a hotline that provides “support services to farm families in crisis.”) Mellencamp has also become a serious painter. His portraits suggest the same preoccupations as his songs, depicting beautiful, sad-eyed figures rendered in muted, earthy tones. One self-portrait, “Pandemic John,” features Mellencamp looking forlorn and slightly peeved. His brow is so furrowed that it appears topographical.

“Strictly a One-Eyed Jack” places Mellencamp in a lineage of artists (Leonard Cohen, David Bowie, even, to some extent, Bob Dylan) who have found new inspiration by reckoning with death. Though rock music has historically venerated youth (“I hope I die before I get old,” Roger Daltrey, of the Who, famously shouted in 1965), its relevance has waned a bit in recent years, as hip-hop and its various outcroppings have ascended. This has perhaps left rock and roll available for a reclamation. Rebellious teen-agers and aging, introspective rock stars share a sense of freedom, an understanding of what’s possible when responsibilities—to the marketplace, to polite society—melt away. A different kind of disobedience might come with age, but it is no less electrifying.

In 2012, the singer and songwriter John Mellencamp was given the John Steinbeck Award, presented annually to an artist, thinker, activist, or writer whose work exemplifies, among other virtues, Steinbeck’s “belief in the dignity of people who by circumstance are pushed to the fringes.” The grace of the marginalized is a long-standing theme of Mellencamp’s writing. The musician, who comes from Indiana and began releasing records in the late nineteen-seventies, is known as a populist soothsayer, an irascible and unpretentious spokesman for hardworking, rural-born folks. Yet Mellencamp has also bristled at this characterization, which is largely rooted in fantasy: men gazing wistfully out the windows of vintage pickup trucks, watching dust blow by, listening to some parched and distant radio station. The image of such “real,” non-coastal Americans has become a useful cudgel for conservatives looking to depict their opponents as élitist buffoons; Mellencamp finds this grotesque. “Let’s address the ‘voice of the heartland’ thing,” he told Paul Rees, whose satisfying biography, “Mellencamp,” came out last year. “Indiana is a red state. And you’re looking at the most liberal motherfucker you know. I am for the total overthrow of the capitalist system. Let’s get all those motherfuckers out of here.”

Besides sharing Steinbeck’s political radicalism, Mellencamp also possesses his instinctive knowledge of just how desolate even the sweetest life can feel. “All great and precious things are lonely,” Steinbeck wrote in “East of Eden,” from 1952. “Sometimes love don’t feel like it should,” Mellencamp sang on the single “Hurts So Good,” from 1982. Mellencamp turned seventy in October, and this month he is releasing “Strictly a One-Eyed Jack,” his twenty-fifth album. “Wasted Days,” the first single, a duet with Bruce Springsteen, is about the despair of aging. “How can a man watch his life go down the drain? / How many moments has he lost today?” Mellencamp rasps. “And who among us could ever see clear? / The end is coming, it’s almost here,” Springsteen adds. Mellencamp’s voice is shredded from decades of cigarettes—it remains an illicit delight to watch him smoke hungrily throughout an entire 2015 appearance on the “Late Show with David Letterman”—and his face has turned long and craggy under his trademark pompadour.

Mellencamp sounds like he’s working through a season of mortal reckoning, though, to be fair, he has been lamenting impermanence since his youth. On “Jack & Diane,” another single from 1982, he sang, “Oh yeah, they say life goes on / Long after the thrill of living is gone.” “Strictly a One-Eyed Jack” is lumbering, bleak, and engrossing. Mellencamp’s voice, once booming and raucous, is now softer, but never gentle. (Vocally, he has landed somewhere between late-career Bob Dylan and early-career Tom Waits.) He is frequently accompanied by acoustic guitar. Age seems to have given Mellencamp license to gripe; he is a poet of ennui, which makes him an apt mouthpiece for a moment when it is sometimes difficult to feel optimistic.

These days, Mellencamp doesn’t care about appearing likable, grateful, or good-natured. “I come across alone and silent / I come across dirty and mean,” he admits on “I Am a Man That Worries.” He delivers each line with the steadfast confidence of a guy who has witnessed a lot of ugliness and won’t pretend otherwise. As he told Rees, “I’ve been right to the top and there ain’t nothing up there worth having.” This sort of honesty—unconcerned with commercial striving; a pure repudiation of the filtered and staged—is rare. It buoys these songs and gives them heart.

Mellencamp was born in 1951, in Seymour, Indiana, with spina bifida, a neural-tube defect in which the spine and the spinal cord don’t develop properly. In the fifties, spina bifida was often terminal. It was standard practice to wait six months or longer to operate on infants with the condition, but, because so many babies were dying before then, a pioneering surgeon performed the procedure on Mellencamp right away. Incredibly, he survived. Rees’s book suggests that this early miracle gave the singer preternatural confidence. “Every day of my life my grandmother told me how lucky I was,” Mellencamp recalled to him. “You get told that enough and you believe it.”

Mellencamp’s family attended the Church of the Nazarene, a punitive Protestant sect that prohibited alcohol and tobacco. Even as a youth, Mellencamp had a reputation for being petulant and cocksure. By the age of fifteen, he was singing in a local band called Crepe Soul, six of whose members were Black. The band’s integration angered some listeners. “They loved us when we were onstage,” Mellencamp told Rees. “It was when we came off they didn’t like us so much.” Mellencamp learned to fight with a blackjack—a strip of leather with a piece of steel sewn into it. At eighteen, he married his high-school girlfriend, Priscilla Esterline. (The two later split, and Mellencamp married and divorced twice more; he has five children.) In 1976, Mellencamp acquired a manager, who suggested that he change his name to Johnny Cougar. He did, reluctantly, and signed a deal with M.C.A. Records. His début LP, “Chestnut Street Incident,” was a flop, and he lost both the manager and the deal. He didn’t become a pop star until 1982, when he released his fifth album, “American Fool.”

Mellencamp was a champion of so-called heartland rock, an earnest, vaguely melancholy mashup of traditional folk music and fractious, boot-stomping rock and roll. The sound was marked, lyrically, by concern for the working class and a realist approach to romance: there are no guarantees in life, so drive it like it’s stolen. The genre’s best songs unfold like short stories, with opening lines that tremble with foreboding. Lucinda Williams begins “The Night’s Too Long,” from 1988, “Sylvia was workin’ as a waitress in Beaumont / She said, ‘I’m movin’ away, I’m gonna get what I want.’ ” On Mellencamp’s “Small Town,” from 1985, he offers, “Well, I was born in a small town / And I live in a small town / Probably die in a small town.” Sometimes there are hints of redemption in the choruses. Often there aren’t.

Throughout the years, Mellencamp’s advocacy for the neglected began to focus on American farmers. In 1985, he, Willie Nelson, and Neil Young started Farm Aid, a nonprofit that puts on an annual benefit festival to bring attention to the plight of small family farms. In 1987, Mellencamp testified before the Senate in support of the Family Farm Act. He said, of frustrated farmers, “It seems funny and peculiar that, after my shows and after Willie’s shows, people come up to us for advice. It is because they have got nobody to turn to.” (Farm Aid operates a hotline that provides “support services to farm families in crisis.”) Mellencamp has also become a serious painter. His portraits suggest the same preoccupations as his songs, depicting beautiful, sad-eyed figures rendered in muted, earthy tones. One self-portrait, “Pandemic John,” features Mellencamp looking forlorn and slightly peeved. His brow is so furrowed that it appears topographical.

“Strictly a One-Eyed Jack” places Mellencamp in a lineage of artists (Leonard Cohen, David Bowie, even, to some extent, Bob Dylan) who have found new inspiration by reckoning with death. Though rock music has historically venerated youth (“I hope I die before I get old,” Roger Daltrey, of the Who, famously shouted in 1965), its relevance has waned a bit in recent years, as hip-hop and its various outcroppings have ascended. This has perhaps left rock and roll available for a reclamation. Rebellious teen-agers and aging, introspective rock stars share a sense of freedom, an understanding of what’s possible when responsibilities—to the marketplace, to polite society—melt away. A different kind of disobedience might come with age, but it is no less electrifying.