Q Magazine: "Crazy Heart" John Mellencamp In Depth Interview

Q Magazine Written By Paul Rees - Pictures By Robert Gallagher

Crazy Heart

One of America’s 10 greatest songwriter, according to Johnny Cash. Others have

simply described John Mellencamp as “ornery, mean and hateful…”

John Mellencamp’s recording studio, Belmont Mall, speaks volumes of its owner.

Tucked off a rural back road 20 minutes’ drive out of Bloomington, Indiana (the

college town where Mellencamp has lived most of his adult life), from the

outside it is rustic and unscrubbed. Its green clapboard buildings are arranged

in a dogleg around a pebbled courtyard. A basketball hoop hangs out front. A

black sign in the car park reads: Reserved for Elvis Presley.

Inside black and white portraits of Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan and, in the toilet,

of James Dean pissing, hang from white walls. There are many citations and a

framed pair of handwritten commendations, one each from Barack and Michelle

Obama. The gold and platinum discs that occupy one room tell of the 40 million

records Mellencamp has sold.

Q meets Mellencamp at his estate, 10 minutes further along the road and set amid

63 acres of pine forest on the shores of Lake Monroe. An accomplished painter

since his youth, he has his art studio here. A corrugated steel structure like a

space-age barn, its interior consists of high beams, dark wooden floors and

antique furnishings. Art tomes and faded photographs of four generations of

Mellencamps fill one glass-fronted cabinet.

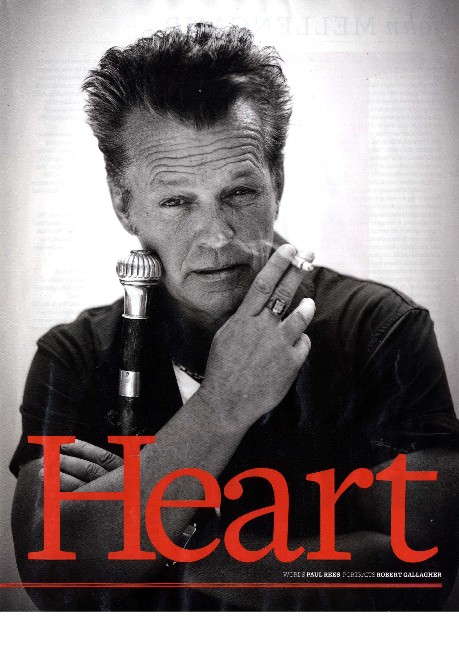

The sound of heavy work boots on steel steps announces Mellencamp’s arrival.

Long perceived of as a Bruce Springsteen rougher sibling, this is precisely how

he appears as he sweeps into the room carrying a battered acoustic guitar and a

Victorian walking cane. He is a short, bullish man; his eyes hidden behind

aviator shades, his arms as thick as slabs of meat. His face, once boyish, is

now more crumpled but still handsome. His head is crowned by a pompadour of

hair. A hacking graveyard cough testifies to the fact that he still smokes like

a chimney.

He squints at Q’s photographer. “You’ve got 30 fucking minutes,” he says by way

of introduction. This noted, he pulls a three-foot blade from top of his walking

cane and swishes it about.

John Mellencamp is notoriously unimpressed with the business of having his

picture taken. The last photographer to visit, an unfortunate gentleman from an

American magazine, was laid out with a single blow when he attempted to

manhandle his subject into position.

But then, Mellencamp’s firebrand reputation precedes him. Ask locals in

Bloomington about their famous son and they will tell of his charitable

contributions to local causes, but also speak more darkly of his apparent

surliness. Many record label executives and collaborators have felt the force of

his fists or temper. Not for nothing did he christen himself “Little Bastard” in

the ‘80’s.

“Back then I was highly strung and very angry,” he says in a deep, husky drawl.

“Always mad at someone, fighting and screaming. Not a pleasant person. I think

it’s in my DNA. I grew up around a bunch of men who were angry. My grandfather,

my dad, my uncles…I resolved to be a better man. I found out in my 30s that

maybe I wasn’t.”

John Mellencamp was born 58 years ago in the industrial town of Seymour, and was

fronting bar bands around Indiana aged 14. At 18 he eloped and got married to

the first of his three wives. His recording career began in the mid – 70’s

under the name of Johnny Cougar (his first manager stopped him from using his

“difficult” given name professionally – he wouldn’t do so exclusively for 15

years). In his own words he made seven albums of “stupid pop songs” and then, in

the mid ‘80’s he got good, mining a rich steam of blue-collar rock anthems. He

and his band became the hottest ticket in America, rivaling his two

contemporaries, Springsteen and Tom Petty, without ever attracting the same

critical acclaim. He would always appear the outsider.

His hot period lasted through to 1993’s downbeat Human Wheels record. Enraged at

his record company’s perceived failure to promote it, he confronted the label

president at a party and punched him. A year later, aged 42, he suffered a heart

attack, having smoked four packs of cigarettes a day for years. Since then he’s

gradually repositioned himself as an American folk singer, the appeal of his

records becoming more selective as exponentially they are heralded.

He doesn’t enjoy being interviewed any more than being photographed, but over

two hours he warms to conversation. When he does, he laughs often in a rasping

wheeze that invariably turns into a coughing fit. On more than one occasion he

will admonish: “Talk up. I’m completely fucking deaf.”

He is reflecting upon how he soldiered for a decade before “learning how to

write songs” and becoming a superstar in the US with 1985’s Scarecrow record.

“My grandfather gave me the greatest advice,” he says, “He told me, John if

you’re gonna hit a cocksucker, kill him. That was his way of saying there’s no

point in trying to do something in life that you’re not going to commit yourself

to. That was where I was at: you’re going to have to kill me to stop me. During

that period, from Scarecrow to [1989’s] Big Daddy I felt bulletproof. Then I had

a heart attack.”

How did that feel?

“Didn’t know I was having one,” he says. “But when I found out, man, I was

pissed. I cussed that doctor from one side down the other. Then I had to get

catheterized. Having a camera shoved up through your groin… That’s when you

realize how vulnerable you are.”

He lights another cigarette.

“You know they may have mentioned something about stopping smoking a couple of

times back then. I’ve just accepted that cigarettes will probably kill me and

that’s that.”

His new album, No Better Than This, is his 21st studio set and was produced,

like its predecessor Life Death Love and Freedom, by T-Bone Burnett, who has

done the same job in piloting Mellencamp deep into American roots music as he

has with another veteran rocker, Robert Plant. Mellencamp learnt from the

album’s stand-up bassist David Roe that Roe’s previous employer Johnny Cash

thought him one of the 10 greatest American songwriters. He takes a more

circumspect view of his status.

“I feel like Jeff Bridges,” he says. “Wonderful actor but he never got his due

credit. There was always someone a little slicker, a little smarter. But he was

always solid.”

Mellencamp’s house is a mile up a dirt track from the studio and he drives to it

in his small green John Deere jeep at teeth-rattling speed. It’s a sprawling

stucco building, one part Mexican ranch house to one part Mediterranean villa.

Huge floor-to-ceiling windows look out onto the expanse of Lake Monroe.

He and his third wife Elaine, a former model, live here with their two sons, Hud,

16 a state boxing champion, and Speck, 15, a budding musician (Mellencamp has

three daughters from his two previous marriages). At weekends locals often boat

past the house, blaring out his music (he says he’s rarely at home then-he also

has two houses in Georgia and “a bunch of properties” in Indiana).

He recalls a more caustic response from this staunchly Republican state to his

2003 song To Washington, one of the first to protest at America’s invasion of

Iraq. He was driving with his eldest son listening to a talk radio station when

a caller rang into say he couldn’t decide who he hated more – Mellencamp or

Osama Bin Laden.

Political activism, he says, is ingrained in the family. He has a picture of his

mother, aged 19, picketing a local cannery. Perhaps his own most lasting legacy

will be Farm Aid, the annual charity gig and organization he co-founded with

Neil Young and Willie Nelson in 1985, which has raised $37 million for America’s

embattled independent famers. “I’m very liberal, almost radical,” he says.

“First time I met Barack Obama I told him, Man, you’re too conservative for me.”

He points out a clearing in the tree line on the far shore of the lake. A few

years back he bought an old cabin over there to do up and use for family

vacations. Once he’d paid for the place, he says, the previous owner sent him

newspaper clippings, explaining how three people had died there in the ‘30’s.

Two brothers got in a fight over a girl; one killed the other with a poker,

before panicking and driving off with the girl, only to crash his car into the

lake, drowning them both.

“The place was haunted,” he says. “I stayed in it for two nights, couldn’t stand

it. You’d hear things, shit would move. Sounds crazy, but it’s true.”

He and his friend, the horror writer Stephen King , have been working on a

musical play based on this story since 2000. Titled The Ghost Brothers Of

Darkland County, he expects it to finally be staged next year. The veteran

Norwegian actress Liv Ullman has been hired to direct. “It will,” he notes,

“either be so fucking good that you can’t stand it, or the worst piece of shit

your ever saw.”

He sold the cabin on years ago. Did he mention anything to the guy who bought

it?

“Not a fucking word.”

The following morning we catch up wit him at a local airfield. For the past two

summers he has toured the US with Bob Dylan, playing minor league baseball parks

and state fairs. Tonight’s show is in Bend, Oregon a former logging town of

52,000 people. The private plane he hires for such trips, a nine-seater jet,

idles on the runway.

On the three hour fight, Q sits opposite Mellencamp and Mike Wanchic, his

guitarist of 35 years. They talk about various ailments afflicting mutual friends

in the offhand manner of men who’ve known each other a long time. “I said to

Elaine, “Sister, I’ve only got 20 years left,” says Mellencamp. “I said, What I

want is for you to lay my body out on a cooling board in the living room like

they used to, and people who want to come and see me lying dead can do so. After

that I don’t care what you do. Just get rid of me somehow. Elaine’s still

beautiful,” he adds, almost as an afterthought. “She could do better than a

cranky old man.”

The vibe at Bend‘s Les Schwab Amphitheatre is more village fete than rock gig.

This picturesque venue on the banks of the Deschutes River amounts to an expanse

of grass with room for 4000 people to sit on deckchairs and picnic rugs,

drinking wine.

Mellencamp and his band take to the stage as the evening sky turns to pink. They

play for 65 minutes. The crowd responds most vocally to 20 year-old hits Paper

In Fire and Authority Song. But it’s more recent songs such as the folk hymnal

Save Some Time To Dream that he sings with most conviction. Early in the set a

security guard tries to forcibly seat a couple on the front row. Mellencamp

wanders to the lip of the stage and jams the neck of his guitar into his head.

“Only way to get the motherfucker to quit,” he determines later.

Afterwards he sits outside the silver Airstream caravan he has towed from gig to

gig. He is dressed in baggy tracksuit bottoms, a pair of reading glasses perched

on his nose. He looks like someone’s bookish uncle.

“Bob panders to no one,” he is saying, nodding towards the stage where Dylan and

his band have begun playing. “He takes no shit, never has and never will. I

really, really admire that in him.”

His assistant brings him a plate of barbecued food. “What makes you think I’m

going to eat that shit?” he asks her. She ignores him. He recalls that her

predecessor, who lasted 20 years, habitually referred to him as mean and

hateful. In a speech inducting him into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 2008

his friend Billy Joel implored him to: “Stay ornery, stay mean-we need you to be

pissed off.”

“Billy called up a bunch of people who’d worked for both of us,” he says. “He

said, John they all said they loved you, but they don’t like you. My conclusion

is I’m hard headed but soft hearted.”

He laughs, coughs, and laughs some more. And then he bids us goodnight and

stalks off to his caravan. A gaggle of people from the tour party is gathered

about it.

“Get the fuck way from my trailer,” he barks. And the he’s gone, cackling to

himself.